I contemplated using the screenshot from Robin Thicke’s music video of “Blurred Lines” where he is standing next to a completely naked dancing woman. Then I thought that probably wasn’t my smartest idea and I like my job. So instead here are some employer-approved blurred lines:

Now back to the topic.

The use of social media and the potential challenges it presents in a workplace context has been recently highlighted by the dismissal of Angela Williamson by Cricket Australia.

Ms Williamson was dismissed by Cricket Australia in June 2018 because she had “lost the confidence of Cricket Tasmania” and her services as the Tasmanian Public Policy and Government Relations Manager were terminated immediately.

The supposed loss of confidence was said to arise from a tweet that criticised a decision by the Tasmanian Government.

It has been reported by various media outlets that in early June 2018, Ms Williamson met privately with a senior member of the government to discuss and lobby for the return of publically funded abortion services in Tasmania. A week after that, the Tasmanian Parliament voted down a motion to re-establish abortion services in public hospitals. Ms Williamson described the decision as “irresponsible… gutless and reckless” on Twitter. There are currently no publically funded abortion services in Tasmania. Ms Williamson had experienced the impact first-hand, having to travel to Melbourne to access publically funded abortion services.

Fairfax media reported that the letter confirming the decision to terminate Ms Williamson’s employment says: “Taking into account your most recent tweet on June 14, and the fact that Cricket Tasmania has now withdrawn its support, we have reached the conclusion that your continued employment with Cricket Australia is untenable”.

Ms Williamson has lodged an unfair dismissal claim with the Fair Work Commission against Cricket Australia. We will be watching closely for further developments in this case and report back.

In the meantime we should be asking questions – Was that tweet disparaging? Was it really so damaging to the confidence her employer could have in her as a government relations manager? Shouldn’t employees be able to express their personal political views?

We all recognise that our employees have private lives and private interests. However, with the prolific use of social media both in the business and personal contexts, the once clear(er) line between personal and professional life are now blurred.

SO WHAT CAN OR CAN’T EMPLOYEES DO?

It depends. The answer won’t be 25 words or less. Everything depends on context and each case will turn on its own facts.

We are yet to see what the outcome of Ms Williamson’s claim is. Below are several examples, in brief, of decisions concerning dismissals that relied on social media use and how it has been dealt with.

PLEASE BE WARNED: I get to use some strong language for a legitimate work purpose (yippee) but some readers may find this distressing or disturbing. If you prefer you may want to avoid reading this part and head straight to the bit about policies…

Fitzgerald v Escape Hair Design [2010] FWA 7358

Ms Fitzgerald posted on her Facebook feed: “Xmas ‘bonus’ alongside a job warning, followed by no holiday pay!! Whooooo! The hairdressing industry rocks man!!!! AWESOME!!!!”

She was dismissed from her work for reasons that included that post.

The Commission found that the post was not a valid reason for dismissal as the post did not name the employer and did not cause damage to the employer’s business. There was not a sufficient connection to the employer that was established.

Further, action was not taken swiftly upon the employer discovering the comment in early January which did not help the argument by the employer that there was detriment to the business. It was relied upon a reason for dismissal in February 2010.

O’Keefe v The Good Guys [2011] FWA 5311

Mr O’Keefe’s Facebook post read: “how the f*** work can be so f****** useless and mess up my pay again. C***s are going down tomorrow”.

Although the employer wasn’t named, the Commission found it constituted serious misconduct because the post directly threatened other employees, and Mr O’Keefe conceded it was directed at one employee in particular. That established a sufficient connection to the workplace.

Glen Stutsel v Linfox Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FWA 8444

Mr Stutsel posted comments on Facebook:

- referring to a muslim colleague as a “bacon hater”

- “You can call it a bit of professional courtesy, I admire any creature that has the capacity to rip Nina and Assaf heads off, shit down their throats and then chew up and spit out their lifeless body!’”

While rather unpleasant, Mr Stutsel’s comments were not found to constitute serious misconduct. It was also not found to be a valid reason for dismissal. At first glance it would appear difficult to reconcile O’Keefe and Stutsel.

In Stutsel, Linfox lacked a social media policy. Also the Commission found that the “bear conversation” in its full context had the flavour of a group of friends letting off steam about work. Interestingly the Commission found it unsurprising that as a Union delegate there may be some uncomplimentary comments by Mr Stutsel about the employer’s managers.

This decision was affirmed on appeal.

Cameron Little v Credit Corp Group Limited t/as Credit Corp Group [2013] FWC 9642

Amongst a number of unsavoury comments, Mr Little posted on Facebook: “On behalf of all the staff at The Credit Corp Group I would like to welcome our newest victim of butt rape, [Employee name]. I’m looking forward to sexually harassing you behind the stationary (sic) cupboard big boy.”

Mr Little argued that dismissal was unfair because they were joke comments made in his own time and there was nothing on his profile that confirmed he was an actual employee of Credit Corp.

The Commission found that the conduct constituted serious misconduct and therefore Credit Corp had a valid reason for dismissal. It was determined that Mr Little’s conduct was not compatible with his duties to his employer and caused damage to Credit Corp’s interests.

Mr Little showed no remorse for his conduct even though he had previously been spoken to about other comments he had posted.

Unsurprisingly, the Commission found that the dismissal was not unfair.

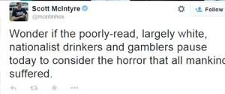

Scott McIntyre v Special Broadcasting Services Corporation t/a SBS Corporation

On Anzac Day, Scott McIntyre made a number of controversial tweets from a personal twitter account including:

- The cultification of an imperialist invasion of a foreign nation that Australia had no quarrel with is against all ideals of modern society.

- Remembering the summary execution, widespread rape and theft committed by these ‘brave’ Anzacs in Egypt, Palestine and Japan.

He had over 30,000 followers on twitter at the time and his personal account indicated that he was a reporter for SBS. He was not rostered on at the time of making the tweets.

Mr McIntyre was dismissed from SBS after posting those tweets, although some media reports indicate he was dismissed because he refused to take down the tweets as directed by SBS.

General Protections Claim

nitially, Mr McIntyre brought a general protections claim under against SBS section 351 of the Fair Work Act. Section 351 of the Fair Work Act relevantly states:

Discrimination

- An employer must not take adverse action against a person who is an employee, or prospective employee, of the employer because of the person’s …political opinion….

Mr McIntyre argued that SBS had contravened section 351 because SBS had taken adverse action (the dismissal) against him because of his political opinion as expressed on twitter.

Unfortunately Mr McIntyre had to withdraw that claim. This was because of a legal error – section 351 also says the protection as stated above “does not apply to action that is not unlawful under any anti-discrimination law in force where the action is taken”. The term “anti-discrimination law” is given a definition listing anti-discrimination legislation. So put another way, as political opinion is not a protected class or attribute covered by the Age Discrimination Act 2004, the Disability Discrimination Act 1992, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 or the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977, Mr McIntyre was not entitled to receive the benefit of the protection under section 351.

Unlawful Termination Claim

After reaching the conclusion that the general protections application was not going to succeed, Mr McIntyre quickly made an application for unlawful termination of employment under a different section of the Fair Work Act – section 772.

Section 772(1)(f) of the Fair Work Act says:

An employer must not terminate an employee’s employment for one or more of the following reasons, or for reasons including one or more of the following reasons:

…

(f) … political opinion…

Mr McIntyre needed to get approval from the Commission to bring the application because he was outside the time limit for doing so, being 21 days from the date of dismissal. In the circumstances, and as the delay was explainable by representational error (i.e. the lawyers said it was an error by them) the Commission granted the extension of time.

However, we won’t know for sure whether or not Mr McIntyre’s argument would have been successful. The matter settled shortly before the hearing was due to commence.

Michael Renton v Bendigo Health Care Group [2016] FWC 9089

Mr Renton posted a comment to a video of an obese woman in her underwear dropping her stomach on to the back of a man on all fours, also in his underwear. In the video, the woman can be heard to say ‘how heavy is that’ and ‘a little horsey’. In his comment, Mr Renton tagged two work colleagues saying: “[employee name] getting slammed by [employee name] at work yesterday!”

While the Commission agreed it was a valid reason for dismissal, in all the circumstances it found that the decision to terminate Mr Renton’s employment for serious misconduct was harsh and therefore he was unfair dismissed.

S v LED Technologies P/L [2017] FWC 1966

Mr S, a Merchandiser at LED Technologies posted on facebook during work hours: “I don’t have time for people’s arrogance. And your not always right! your position is useless, you don’t do anything all day how much of the bosses c*** did you suck to get where you are?”

LED Technologies mistakenly believed that the post was referring to employees at the business, but in fact it was referring to a situation that was faced by his mother at a different employer. Mr S wasn’t given an opportunity to explain his conduct he was just told in a short telephone conversation “you’re fired”.

The Fair Work Commission commented that:

- while the language used by Mr S was offensive and vulgar, such language was increasingly used in everyday situations

- there was no proof that the post was directed at LED Technologies or its employees or was sufficiently connected to work at LED Technologies.

- Mr S did not appear to have been provided with the social media policy.

The Commission found that LED Technologies did not have a valid reason for dismissal and it was therefore harsh, unjust and unreasonable. Mr S was awarded compensation.

SO, LET ME GUESS: I NEED ANOTHER POLICY?

Okay, I get it, this is a common theme in these articles. We do, on a fairly regular basis, encouraging our clients to develop a range of policies and procedures. People probably think that is all you need to know to practice employment law.

But for those who haven’t received had the pleasure of our lecture, all employers should have policies so employees know what the expectations are and what happens when they are not met. Normally a policy on Social Media Use and/or something about social media use in the Code of Conduct are advisable.

Employers should sets an expectation that employees need to refrain from any activity, including in their private life, that is likely to result in harming the business of the employer, its reputation or its customers. That is a reasonable expectation, not a dictatorial intrusion into employee’s personal lives.

Don’t forget the training! Training needs to be offered and provided to employees about these issues. It is particularly important to bring it to the attention of those employees who don’t know the world that existed prior to having a detailed photo record of your friend’s dietary habits.

Employees can’t be prevented from using social media platforms altogether, be given a list of “banned tweets/posts” or be given a list of topics they can’t post about. It is not only be an unreasonable intrusion for an employer to

try to censor employees in their professional and personal lives, it would be impossible to come up with a definitive list of unacceptable/inappropriate words and would take a dedicated and well trained team of Facey-Insta-Tweet-Police to enforce compliance.

Employees should be encouraged to exercise a little self-protection and discretion and to “think before you post”. They should be asking themselves whether their posts pass the “nanna test” – if your nanna would be offended or you would be embarrassed for your nanna to read your post, don’t post it.

GOT MY POLICY, NOW TO DEAL WITH MY EMPLOYEE…

Before you do anything, we suggest you get some legal advice.

Regardless of any personal or moral feelings you have about an employee’s conduct online, employers should ask themselves a series of questions:

- Do I know the full context of the conduct?

- Is there a breach of policy? Is the employee aware of the policy?

- Is there enough of a connection between the conduct and our business or the employee’s work?

- Is our business and its reputation potentially going to be damaged by the conduct?

- Were the comments, video or tweet etc made in the public domain and who could see it?

- Were the comments seen by or refer to other employees, clients or associates of the business?

- Was the conduct unlawful or potentially unlawful in nature e.g. discriminatory, harassment, bullying?

This is a very tricky call for employers to make and an issue that can be difficult to manage.

Get in contact if you have any thoughts on how Ms Williamson’s case will pan out…

Feature Image from sourced from https://todaytesting.com/